*TICKETS ARE SOLD OUT*

Patrick Watson is the name of both a man—born in Lancaster, California in 1979—and his band, which he formed in his adopted home of Montreal in the thick of the city’s early-aughts indie-rock boom. Like fellow scene linchpins Arcade Fire and The Dears, Patrick Watson built their brand on a foundation of anthemic songcraft, artful arrangements, and heart-swelling orchestration, as demonstrated on their 2006 Polaris Music Prize winner, Close to Paradise.

Patrick will be supported by opening act Al Olender.

Saturday September 16 2022 / 7:00pm Doors Open

In the Barnspace at Race Brook Lodge

864 South Undermountain road ( AKA Rt 41 ) Sheffield, MA

Ticket Price: First 50 tickets $30 / Next 50 tickets $40 / Final 20 tickets $50 - CLICK FOR TICKETS

Race Brook Lodge is a hidden gem in The Berkshires, at the foot of Mt. Race and a short hike from the Appalachian trail. The yoga & event barn at Race Brook is simultaneously rustic and sublime, steeped in hundreds of years of New England history. The Stagecoach Tavern is unpretentious fine dining, exquisite farm-to-table cuisine in a relaxed atmosphere. Much of the food is sourced from Race Farm, right on the property!

DINNER RESERVATIONS AT THE STAGECOACH TAVERN

Artist Bios

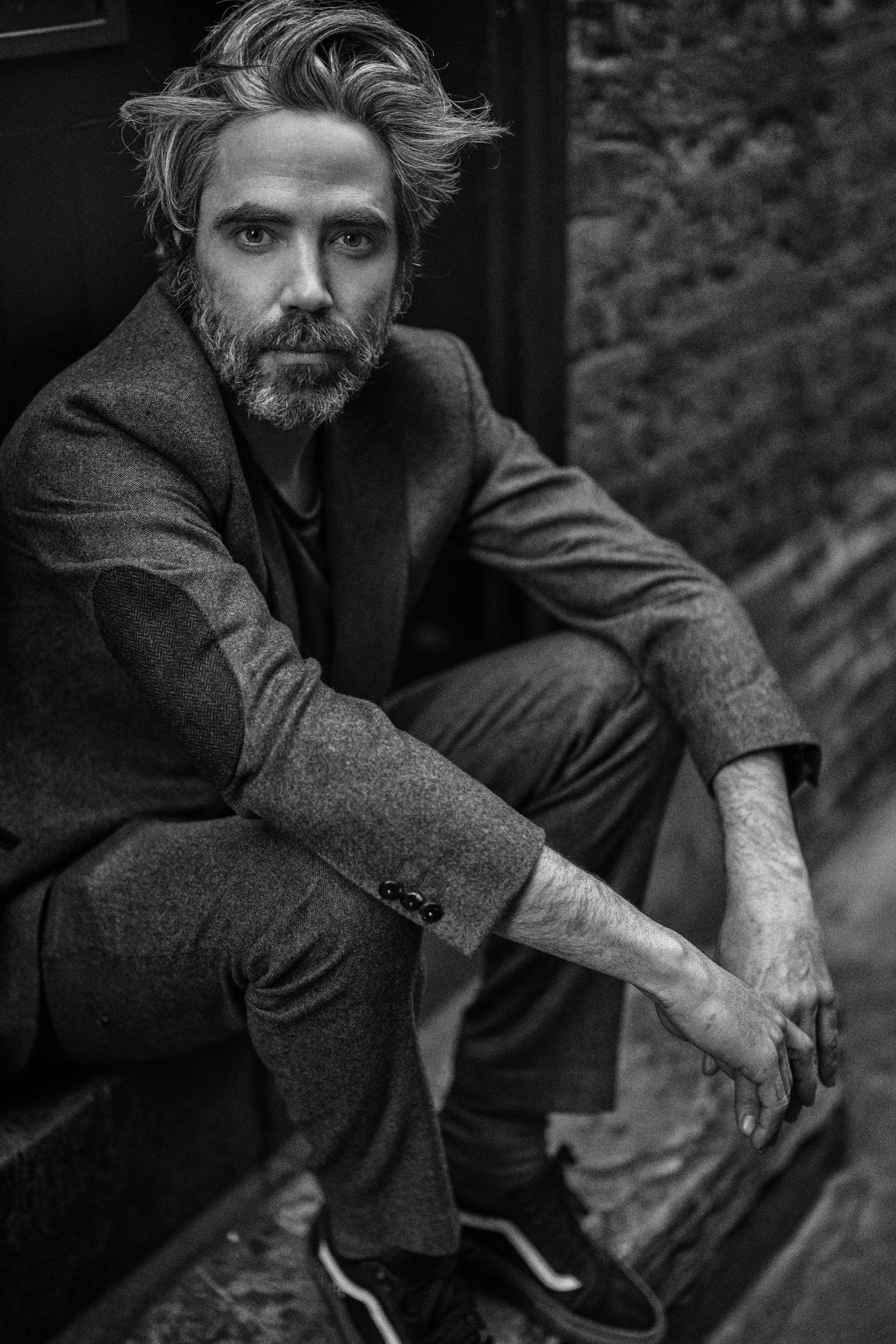

Patrick Watson

Once there was a boy named Patrick Watson who was born on a military base in the Mojave Desert. His father rode around in planes carrying bombs, waiting for a command to drop them that never came. He was the baby in a family of five, which would include a future figure skater, an engineer and an air force pilot, but he was seven years younger than his next older sibling. The trouble with being born this late into a family is they have all already gone mad, and they are engaged in domestic dramas, chasing each other around with knives. He was left to make too many assumptions about love and life on his own, and he still has the philosophy of a wise beyond their years wide-eyed child.

The family moved to Hudson Quebec when Patrick was four. He was asked by an old gentleman by the name of Frank Cobatt to sing in the church choir. Perhaps they met in the cough drop section of the local grocery store. And Patrick sang in the church and his little boy’s pretty, melancholic voice broke everyone’s heart. And the choir director had him sing at the foot of a grave at a funeral. Because there is something in his voice that captures all the lovely things in life we can only hold onto temporarily and how their transience is what makes them wonderful.

Patrick started playing piano when he was a child, of course. The piano used to belong to a boy named Gordon. The boy would appear as a ghost and teach Patrick how to play in the middle of the night. Even if Patrick played at three in the morning, his mother never interrupted these vital lessons. He showed me the photo of Gordon who looked, more or less, like a terrifying psychopath with tuberculosis who probably slit his whole family’s throats while they were sleeping. But I did not say so.

Patrick says he became a singer by accident. He thought he would compose scores for others to play, which seems like an odd thing to say because he is so clearly sprinkled with the pixie dust that causes a person to be transfixing on stage. And it’s now hard to imagine Montreal without the soundtrack of his songs.

But he met the artist Brigitte Henry who was taking surreal underwater photographs of people in their clothes to make a book. This seemed like very important business to Patrick, so he made music for her exhibition. They performed the show at the porno movie theatre Cinema L’Amour. It was sold out. Brigitte Henry still designs some of his album covers, including this one.

Patrick likes to hang on to people. He met his first guitar player Simon Angell playing guitar on the small streets of Hudson. In his first jazz class at college he walked in and Robbie Kuster and Mishka Stein were both sitting there. It was as though they were all waiting for each other. They would play together for the next twenty years.

While they were working on his first album, the band lived in an abandoned church. They were kicked out for ringing the church bells when homeless people came in to be married, waking all the neighbours up in the middle of the night, in a misguided attempt to let them know love existed.

They opened up for James Brown where they learned to manage a large crowd. Every day before a concert James Brown and his team would hold hands and pray the show would be amazing. This taught the band that being on stage is a humbling honor and a music show is where people come to have a mystical experience. In the end, it was not so different than when he sang in church as a boy.

While writing this new album, the drummer Robbie left, Patrick and his partner separated, and his mother passed away. Much of this album is about having a wave knock you over when you realize that everything you have in life can be wiped away in a moment. He brought a notebook underneath the waves and composed tunes about melancholy while listening to the lonely hymns of mermaids. And the songs are about how sometimes you have to sing a love song to yourself when no one else will. Melody Noir is about writing a song to the hole inside us all.

Some of the songs, including Turn out the Lights and Look at You, are about falling in love again and learning how to be intimate in a new way. And how surprising it is that, although life can change, it can turn out to be better in so many ways than you could ever have imagined. And, ultimately, the album is about rebuilding your life from scratch.

The songs are marked by the idiosyncratic personalities of each of his band members. Mishka Stein grew up in the Ukraine where he wore little suits and accidentally set his building on fire, but he did a brave job helping the firemen put it out. A sweet Soviet latchkey boy, he spent much of his time watching Russian cartoons. The influence of the absurd anthemic melodies of those cartoons can be felt in the songs, particularly Look at You and Melody Noir.

Joe Grass, who has been playing guitar and pedal steel since Loves Songs for Robots, is a jackknife of sounds. He always creates a distinctive voice within the band's particular brand of music. Evan Tighe landed magically at the perfect moment to take up the drums. The band was very lucky to find such a great drummer in time.

Patrick also worked with Leonard Cohen on one of his last songs before the legend passed away. This had a profound influence on the way he writes lyrics and the possibilities of poetry in song. The collaboration influenced his vocal delivery to be more dry, to have less notes and to simply deliver the words.

The beginning artist's craft is so intuitive and odd, drawing from a trunk of recipes for happiness and hope. They begin with an idea that the world is good and things and love will work out. The mature artist creates from a place of melancholy and understanding of foibles and accepting a story that has already been written. It’s the difference between singing a solo at a stranger’s grave as a child and singing one at your own mother’s funeral.

It’s the same magical and sweet Patrick Watson on this album, but each of the feelings are deeper and dive down to stranger places, where even happiness seems impossible to bear. So the album moves from a dark place of loss to one of hope and magic and new love. The way you thought life was going to work out, but never does. Then it sometimes turns out to be more beautiful and surprising once it is broken.

Al Olender

There’s nothing scarier than being honest with yourself. For singer/songwriter Al Olender, facing her fear of the truth has been a cleansing, often cathartic process that’s led to the kind of revelations she had previously thought unobtainable. On her debut full-length album Easy Crier, the Upstate New York based artist asks: what happens if we vow to never tell a lie, ever again? Charting the daunting territories of staring your demons right in the face and prodding at the ugly parts of your reflection, Olender pieces together her most vulnerable moments to produce a celebratory and beautiful rumination on grief, and reminds us of the power that comes in really getting to know yourself.

The catalyst for this renewed outlook stems from the sudden loss of her older brother. As a huge supporter of Olender’s musical talents from the very beginning, he would often invite his friends over and encourage a then-teenage Olender to play her “angsty love songs” for them. “Everything that I do musically revolves around my brother,” she says. “It's like every single thing I do in my life – my brother is so much in the front of my mind.”

The introduction for Easy Crier comes with “All I Do Is Watch TV,” a darkly humorous comment on the unmoored early stages of losing a loved one, way too soon. “I read a book on grief, it told me to lay in bed,” she laments over a chromatic, repetitive melody – the kind that perfectly mimics an untethered, sped-up montage-like existence, as she watches true crime and buys a Big Gulp just to spill it on her bedroom floor. Here, she jabs at the numbness protecting her heart. “Nothing fixes grief,” she explains. “It transforms. Sometimes it's like a giant glooming thunder cloud and sometimes it's like a tiny little raindrop.”

On the folky, pop-infused banger “Keith,” Olender confronts her sorrow, as fond memories are abruptly interrupted by a crashing cymbal and animated percussion: an ever-increasing heart rate capturing Olender’s inner-chaos as she witnesses a well-meaning funeral guest showing off a new tattoo. Later, on the devastatingly gorgeous closer “Mean,” a sparse, acoustic arrangement offers a platform for a rousing vocal performance, each note a grief-stricken consolation. “I’m older than my older brother, but I’m not old enough,” she shares softly, searching for someone to keep her safe. Olender strives to use her voice for connection and healing, for herself and for anyone else who’s listening.

Olender recorded at The Church in Harlemville, NY, entrusting the skills of producer and engineer James Felice (Felice Brothers). Felice also lent his skills on keyboard, accordion and piano, with Jesske Hume (bass/synths), William Lawrence (drums/guitar), Ian Felice (guitar), and Alejandro Leon (bass) also contributing. The album’s sonic universe sees delicate keys dance alongside acoustic plucks, later welcoming brooding strings and lush, expansive harmonies. It’s these kinds of arrangements that perfectly capture the sonic personality of Easy Crier: it’s both tender and invigorating, soothing yet anthemic. Describing the arrangements as a “conversation with friends,” it’s a testament to what can happen when you surround yourself with those who totally, and willingly, understand your artistic vision.

Easy Crier isn’t an album about death. It’s an album about unending love. It wipes away the mask we put on for others and instead, embraces the exhale that comes from spilling your guts. It’s the moment in your favorite rom-com when they finally admit their feelings for one another, and kiss in a way that only seems to happen in movies; on Easy Crier, Olender plays both parts. There are moments of ease, and exploring the often fine line between funny and sad that makes Easy Crier a portal for relief, whether that’s through tears of joy or pain. It’s an album that takes each shattered, heartbroken piece and puts them back together to form a strangely beautiful mosaic. “It’s a love letter to everything I’ve lost,” she says. “And forms a real insight into how telling the truth has truly changed my life.” Here, Olender is finally letting herself feel everything all at once, no matter how uncomfortable or scary it can be.